Equinox Partners, L.P. - Q2 2018 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

PERFORMANCE & PORTFOLIO

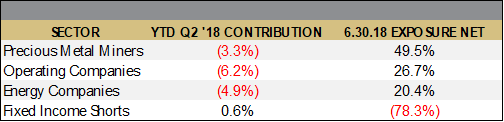

Equinox Partners declined -4.4% in the second quarter of 2018. Through July 30, the fund was down -16.7% for the year to date.

While our fund has performed poorly for the year to date, the companies we own are performing well. Accordingly, the valuation of our portfolio is compressing. As of June 30, our operating companies were trading at 12.7x estimated ’19 earnings, our mining companies at 3.7x estimated ’19 cash flow, and our energy companies at 4.6x estimated ’19 cash flow. During the second quarter, we purchased two precious metals miners, a bank in Georgia, an energy company operating in the U.S., and sold short a U.S. tech company. We also exited a Mexican mining company and reduced our operating company long exposure from 32.5% to 28.7%.

gold

“Even if it works, you’re a jerk.” — Charlie Munger on gold

Conventional wisdom is that gold investors hope bad things will happen. They pine for a trade war, uncontained inflation, central bank missteps, or more or less anything awful that will drive investors to buy gold in droves. Gold investors not only hope for the worst but are incapable of appreciating the progress humanity has made, which is why they cling to their antiquated monetary technology. In Munger’s opinion, this antisocial worldview is so distasteful that it merits opprobrium even if proven right.

Needless to say, we disagree with Munger. The gold investors we know, like more or less everyone else, hope for the best. But, unlike most everyone else, gold investors refuse to believe in the end of financial history. For gold investors, there is nothing novel about government efforts to free our financial system from the credit cycle. Financial history is replete with such attempts. Financial history is also replete with their failure and evidence that these noble undertakings tend to fail spectacularly just when the ever-upward slope of progress seems to be a foregone conclusion.

As global investors, we are regularly reminded that progress is not linear and that the economic cycle has not been repealed. This conviction comes from having lived through more economic cycles than most domestic investors even notice. From the Asia Crisis of 1997, to the Russia Crisis of 1998, to the end of the Real Plan in 2002, to the Argentine Crisis of 2006, to the European Bond Crisis of 2011, to the Turkey Crisis of 2018, we see no evidence that economic cycles are a thing of the past. Moreover, our analysis of these crises reveals two common ingredients: over confidence and over leverage—two qualities that the developed world currently has in spades.

Economic cycles, which remain an accepted fact of life in emerging markets, are increasingly viewed as an avoidable policy error in the developed world. It is almost as if there are two types of countries which are fundamentally unequal. There are countries that remain subject to cyclical vagaries, and there are a handful of core developed world countries subject to a new set of more benign economic rules. Chief among these new rules is that financial stress always benefits the core. This is true even if the stress originates in the core. For example, were the United States to run a large, pro-cyclical fiscal deficit, it would place stress on the U.S. Treasury market which in turn would put even more stress on foreign dollar borrowers which would drive a flight to safety which would in turn buoy the U.S. Treasury market.

While we certainly appreciate the well-worn trading patterns underlying these new economic rules, we are quick to point out that the developed world’s elevated status in global capital markets is not a result of superior policy making. Rather, at its heart, the developed world’s privileged status stems from its ability to take on ever more debt without spooking creditors. This accident waiting to happen, in our opinion, has now gone on so long that many observers actually mistake it for progress. But, why, we ask, must progress involve quite so much debt? Why, for example, nine years into a global, synchronized economic expansion must the world add $8 trillion of debt in a single quarter? From our perspective, this continued reckless accumulation of debt does not signal uninterrupted progress, but instead a deeply destabilizing force with which few market participants are inclined to grapple. Dave Rosenberg’s commentaries, to his credit, have been an exception to this rule:

This entire cycle was built on a mountain of debt that likely never does get repaid, but has to be serviced nonetheless. Consider that at the peak of the last credit bubble, the level of outstanding debt at all levels of society – household, business, and government – totaled $27 trillion or about 225% relative to GDP. Fast forward to today and that number has soared to nearly $50 trillion or 250% of GDP. So look at what happened – the USA merely added more debt to an existing debt bubble. For all the bravado about this long cycle we have enjoyed, it was accomplished on a credit bubble that makes what happened in the 2002-07 mortgage mania look like a walk in the park. The main message being that the economy is more susceptible today to even moderately higher interest rates, which is what we are now experiencing, that at any other time in modern history. Just remember – interest rates exert peak impact with lags. My advice therefore is to not extrapolate what we just saw in the second quarter GDP report, but to instead treat it as a fond memory.

- Breakfast With Dave, July 31, 2018

Amidst this rapid increase in debt, it is galling, but not surprising, that the Federal Reserve has chosen to champion its commitment to financial stability. Galling because if there is one thing a central bank should do to maintain financial stability it is to contain system-wide debt. After all, if adding more debt was a sustainable way to achieve financial stability, why didn’t central bankers of the past also pursue this course? The flippant answer is that in the past the bond market wouldn’t let them. The more troubling answer is that past central bankers weren’t arrogant enough to believe that they could subdue the economic cycle or brazen enough to paper over downturn after downturn knowing full well that the resulting increase in debt would inevitably cause a larger future problem.

The age-old tradeoff between pain today in lieu of more pain tomorrow now seems passé, but this tradeoff was largely why central banks of the past accepted or even initiated recessions. They knew that as painful as a recession might be that financial retrenchment was sounder than the alternative. Today’s central bankers, by contrast, argue that the right policy can simultaneously optimize employment, inflation, and financial system stability indefinitely. Seasoned investors sense that not only is this too good to be true but the effort to achieve this combination of outcomes will eventually create problems that even central bankers cannot solve. That said, after a decade of central bankers’ successful management of the economic cycle, most investors have given up waiting for the eventual failure of their policies.

For those who have not given up, gold is just one among many ways of registering disbelief in the sustainability of the status quo. So, why are gold investors singled out for criticism by Munger and others?

Trivially, short-sellers and traders of derivatives are buying what Wall Street is selling. So, while they don’t agree with the consensus, they are still participating in the financial ecosystem. Gold investors, by contrast, are signaling that something is wrong not just with asset prices but with the financial system itself. For many, this is seen as unhelpful. It is one thing to say that financial assets are overvalued, it is an entirely different thing to say that the very structure of the market is deeply flawed, with the latter offense being antisocial enough to merit condemnation even if it is right.

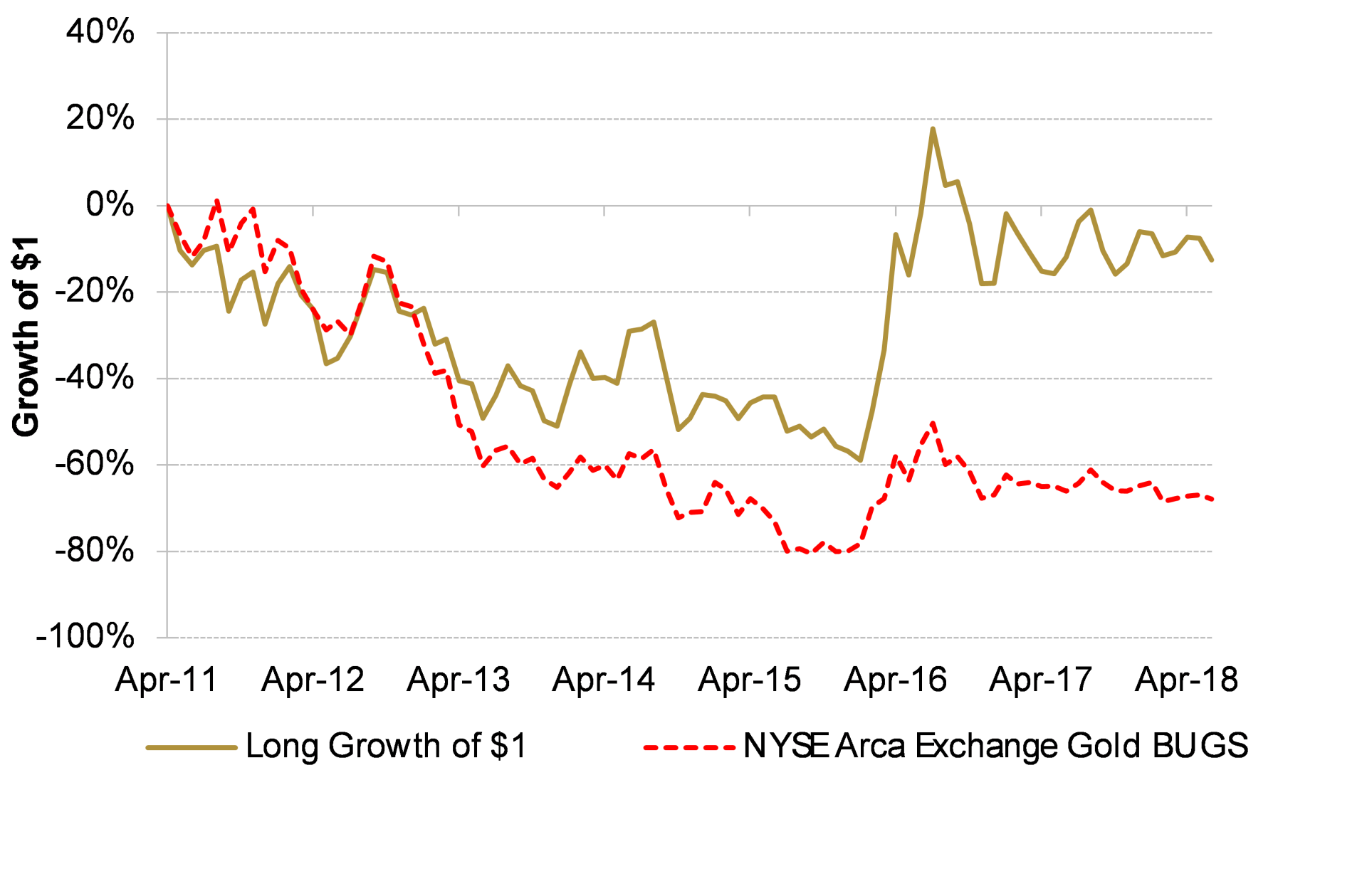

Equinox Partners, of course, owns no gold, only gold and silver mining companies. As we’ve written before, this strategy has enabled us to add value while we wait for gold’s unique financial attributes to regain wider appreciation. While the topline results of our mining investments have been disappointing, we’ve undisputedly added value over the past seven years. Specifically, from its monthly peak in 2011 through June 30, 2018, the gold mining stock index (HUI) has declined 67.6%. Over that same period, our gold and silver investments are down just 12.5%.

Having preserved our partners’ capital through the depths of an extended and severe bear market in gold and silver mining companies, we are particularly well positioned to benefit from a recovery in the sector. Most notably, the long-term partnerships we’ve developed with the better-managed, better-governed companies that have resulted in our outperformance in the ongoing bear market in precious metals miners should also translate into our outperformance in the next bull market.

Sincerely,

Sean Fieler Daniel Gittes

[1] Sector exposures shown as a percentage of 06.30.18 pre-redemption AUM. Performance contribution derived in US dollars, gross of fees and fund expenses. Interest rate swaps notional value and P&L included in Fixed Income. P&L on cash excluded from the table as are market value exposures for derivatives. Unless otherwise noted, all company data derived from internal analysis, company presentations, or Bloomberg. All values as of 06.30.18 unless otherwise noted.

[2] IIF, Global Debt Monitor – July 2018

[3] The junior gold mining index, GDXJ, by comparison, is down 76.9% from its month-end April 2011 peak through June 30, 2018.

Equinox Partners Investment Management, LLC | Information as of 12.31.24 unless noted | *SEC registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training

Equinox Partners Investment Management, LLC | Site by Fix8