Equinox Partners, L.P. - Q1 2023 Letter

Dear Partners and Friends,

PERFORMANCE

Equinox Partners declined -4.2% in the first quarter of 2023.

Visit our performance page to view the Equinox Partners, L.P. fund summary in more detail.[1]

bernanke's legacy: quantitative easing with inflation

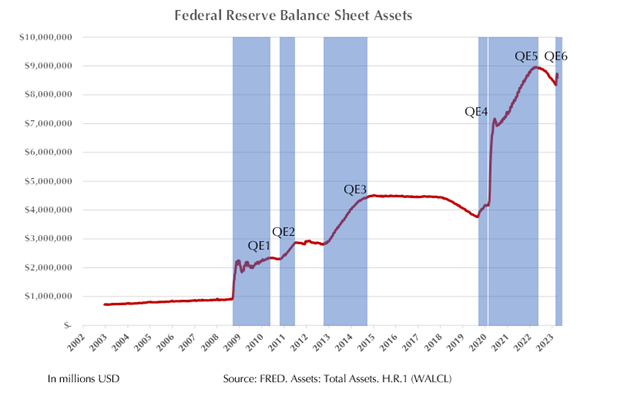

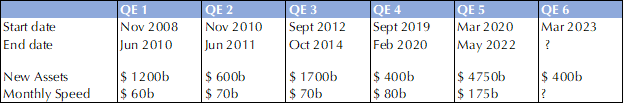

In the fall of 2008, Chairman Bernanke initiated the first round of quantitative easing (QE) as an emergency measure to stop a disorderly credit contraction. Concerned that the new liquidity would stoke inflation, the Fed requested the authority to pay interest on reserves held at the Fed. On October 3rd of 2008, President Bush signed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act into law, and three days later, on October 6th, the Fed availed itself of its new power to disincentivize the banking system from leveraging the money the Fed was about to create.

The payment of interest on excess reserves will permit the Federal Reserve to expand its balance sheet as necessary to provide the liquidity necessary to support financial stability while implementing the monetary policy that is appropriate in light of the System’s macroeconomic objectives of maximum employment and price stability.

- Federal Reserve Board of Governors, October 6th, 2008

Bernanke’s plan to offset the inflationary impact of QE worked brilliantly. The banks grew their reserves at the Fed rather than their loan books, inflation remained anchored, and within six months asset prices bottomed. The results were so good that rather than returning to normal monetary policy, Bernanke began making the case for QE2. Bernanke and his colleagues at the Fed knew that they had not articulated a credible strategy to reduce the Fed’s balance sheet and that failure to unwind QE might impair the Fed’s credibility. They went ahead anyway.

Another concern associated with additional securities purchases is that substantial further expansions of the balance sheet could reduce public confidence in the Fed’s ability to execute a smooth exit from its accommodative policies at the appropriate time.

- Federal Reserve Board of Governors, August 27th, 2010

Just five months after the end of the Fed’s initial $1,200 billion round of QE, Bernanke launched a second round of QE. His protegee at the Fed, Kevin Warsh, voted for the program out of respect for his mentor, but actively campaigned against QE2 and tried to press his colleagues into opposition: "If I were in your chair, I would not be leading the Committee in this direction, and frankly, if I were in the chair of most people around this room, I would dissent." Warsh followed up his private opposition with an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal arguing for strict limits on QE. When that failed to convince his colleagues to change direction, he resigned from the Board of Governors. Thomas Hoening was the only member of the FOMC to vote against QE2. With unemployment still at 9.8% and inflation still anchored, the other members of the FOMC believed that the economy could digest a second round of QE. They were right.

In the summer of 2012, fifteen months after QE2 ended, Bernanke initiated a third round of QE. By this point, Bernanke and his colleagues at the Fed were obviously enamored with QE. But, sensing that the unprecedented actions of the Fed might end badly, Bernanke felt compelled to inform the public of the Fed’s pure motives, commitment to public service, and sensitivity to data. More importantly, Bernanke still believed that he could begin extricating the Fed from QE while he was still Fed chair.

In June of 2013, with just seven months left in his second term as chair, Bernanke announced his intention to reduce the QE3 asset purchases to $65 billion per month from $85 billion per month and wind down the program entirely by mid-2014. This announcement prompted a violent reaction in the market memorably dubbed the ‘taper tantrum’. In the face of market volatility and widening credit spreads, the Fed reversed course, postponing the reduction in the third round of QE until January of 2014.

While Bernanke’s serial balance sheet expansions were all technical successes on their own terms, they created a political appetite for QE that the Fed has was unable to control. Bernanke thought he was keeping the Fed free from politics by making “tough decisions, based on objective, empirical analysis and without regard to political pressure.” Regardless of his intentions, the opposite occurred. His multiple rounds of QE without causing inflation erased a long-standing political taboo in Washington against money printing. The resulting increase in political expectations of the Fed became abundantly clear when President Obama searched for Bernanke’s successor.

Sensing a free lunch, President Obama floated the idea of elevating the most liberal member of the FOMC to succeed Bernanke. Historically, such a trial balloon would have elicited a sharp rebuke from the bond market. Instead, the opposite happened. The bond market loved the idea. Janet Yellen even campaigned for the promotion by extolling the virtues of QE. Importantly, the Senate confirmed her without a partisan fight. Senator Bob Corker, the junior Republican Senator from Tennessee, quietly rounded up eleven Republican votes for her confirmation. His efforts not only avoided a political debate of QE, but instead demonstrated bipartisan support for the policy.

This bipartisan support for QE extended beyond the Obama administration and became overwhelming during the Trump administration. While President Trump often railed against the Fed’s easy-money policies while on the campaign trail in 2016, once in office he wanted a Fed that would keep the money flowing. That meant sidelining the hard money Republicans such as Kevin Warsh and even John Taylor, and instead selecting Jay Powell—a nominal Republican who had been appointed to the Fed by President Obama and who had voted for multiple rounds of QE.

Powell, after an early attempt to normalize interest rates in 2018, lived up to his promise as a flexible central banker. He delivered a fifth round of QE in 2019 in the form of $400 billion of repurchase agreements. This was the most surprising burst of QE in some ways, because in the fall of 2019 the macroeconomic indicators were strong, i.e. the stock market was up 12% on the year, unemployment was at a secular low of 3.5%, and GDP was growing at a 4% clip. But when the Secured Overnight Financing Rate amongst banks spiked from 2.43% to over 9% on September 17th, and the Fed stepped into to calm markets by buying $75 billion of repos. This massive liquidity injection did not immediately calm markets, and the Fed continued to buy repos until it had injected over $400 billion into the markets.

The Covid crisis, just six months later, elicited a round of QE so massive that it finally rekindled inflation. While other factors such as the supply chain and fiscal deficits were at play, the Fed’s insane $3 trillion of QE in three months sticks out as the proximate cause of the inflation problem. The resulting combination of the Fed’s largess, government spending, and lockdowns induced the American savings rate to spike from 8.3% to 33.8% and drove a 26% year on year increase in M2 money supply.

Despite the lingering inflationary effects of QE, the consensus today is not that QE is fundamentally flawed, but simply that we’ve found its limits. Talk of MMT has gone away, but the policy option of expanding the Fed’s balance sheet remains an entrenched policy option. The Fed’s recent decision to discount Treasuries held by banks at par following the FDIC’s seizure of Silicon Valley Bank received little pushback, and Bernanke just did another victory lap when receiving his Nobel prize in Economics. The question for investors is not how QE is viewed today, but whether today’s broadly favorable view of QE survives the next phase of monetary policy during which QE will be more compelled than voluntary.

In an ironic twist, the Fed’s 2008 decision to pay interest on reserves, which was so crucial to prevent the early inflationary effects of QE, is now forcing the transfer of hundreds of billions annually to the private sector. While paying interest on reserves in 2008 was disinflationary when at the time policy rates were zero, paying interest on reserves today is decidedly inflationary. Specifically, 5% on the $5.8 trillion of reserves and repurchase agreements the Fed currently holds on its balance sheet causes a $292 billion transfer to private financial institutions annually. Moreover, this rate of QE arithmetic gets higher as interest rates go up—a particularly toxic dynamic.

By itself a $292 billion annual cash injection is probably manageable in a $23 trillion U.S economy. The real problem arrives when this new baseline of transfers from the Fed is combined with another round of blowout deficits that must once again be financed by the Fed. This, unfortunately, seems about to happen. The Federal government just posted a $1.1 trillion fiscal deficit for the six months ending March 31st, a 65% increase from the prior year period. If this percentage increase versus the prior fiscal year holds, America’s fiscal deficit for the twelve-month period ending September 30th will top $2 trillion. An average recession that elicits countercyclical spending and a further decline in federal tax receipts could double that number. With foreign central banks no longer buying and our domestic banks reducing their interest rate exposure, the only plausible home for a growing supply of treasuries is the Fed’s balance sheet—QE7. Markets are sanguine about this scenario, we are not.

Sincerely,

Equinox Partners Investment Management

[1] Please note that estimated performance has yet to be audited and is subject to revision. Performance figures constitute confidential information and must not be disclosed to third parties. An investor’s performance may differ based on timing of contributions, withdrawals and participation in new issues.

Corresponding End Notes to above hyperlinks

- Monetary Policy since the Onset of the Crisis. Jackson Hole, August 31, 2012 and Transcript of Chairman Bernanke’s Press Conference. September 13, 2012

- Concluding remarks at the Ceremony commemorating the Centennial of the Federal Reserve Act. December 16, 2013.

- What Happened in Money Markets in September 2019. Board of Governors, February 27, 2020 and Fed Preps Second $75 Billion Blast With Report Markets Still On Edge. Bloomberg, September 17, 2019.

- FRED

- The Fed pays interest on $3.16 trillion of bank reserves and on another $2.67 trillion of interest-bearing reverse repurchase agreements.

- U.S government posts $378 billion deficit in March

- CBO Budget Projections

Unless otherwise noted, all company-specific data derived from internal analysis, company presentations, Bloomberg, FactSet or independent sources. Values as of 3.31.23, unless otherwise noted.

This document is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy interests in any product and is being provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as legal, tax or investment advice. An offering of interests will be made only by means of a confidential private offering memorandum and only to qualified investors in jurisdictions where permitted by law.

An investment is speculative and involves a high degree of risk. There is no secondary market for the investor’s interests and none is expected to develop and there may be restrictions on transferring interests. The Investment Advisor has total trading authority. Performance results are net of fees and expenses and reflect the reinvestment of dividends, interest and other earnings.

Prior performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. Any investment in a fund involves the risk of loss. Performance can be volatile and an investor could lose all or a substantial portion of his or her investment.

The information presented herein is current only as of the particular dates specified for such information, and is subject to change in future periods without notice.

Equinox Partners Investment Management, LLC | Information as of 12.31.24 unless noted | *SEC registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training

Equinox Partners Investment Management, LLC | Site by Fix8